As Darker Grows The Night

BY PETER `TAYLOR

Source: Taylor P. (1975) As Darker Grows the Night. Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, Auckland.

When Peter Taylor decided to retire from the sea and settle down to married life, he did not make a very drastic move. Joining the lighthouse service, he was posted in 1958 to Moko Hinau, a rugged island jutting from deep water off the east coast of North Auckland. Here he and his wife Marita were introduced to the joys and frustrations, the occasional dangers and compensating pleasures, of life "in round rooms" far away from the crowds.

From Moko Hinau in subtropical waters to Nugget Point under snow was a change that would have daunted many people, but the Taylors, fortified by a sense of humour and a strong family spirit, survived and flourished. Then came the move to the comparative civilisation of Tiritiri, at Auckland's front door, where an accident was to end Peter Taylor's term with the lighthouse service.

This is a lively and cheerful account of a challenging, often adventurous life far from the settled pattern of today's suburbia. And, with the manned lighthouses on the New Zealand coast gradually being converted to automatic units, it is a life which will soon belong to the past alone.

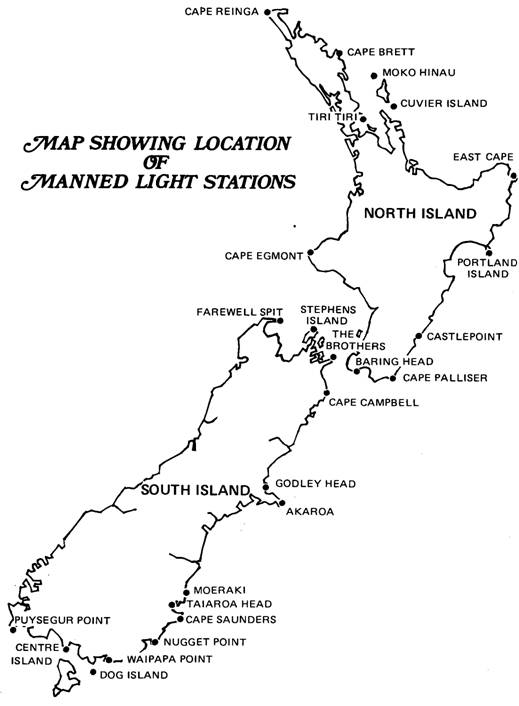

The second part of As Darker Grows the Night contains photographs and notes, based on thorough research, on the history of each of the twenty-five manned lighthouses on the New Zealand coastline. It shows how man, often with considerable success, has attempted to overcome the danger of treacherous coasts, storms and other hazards, allowing our coastal waters to be used for commerce and pleasure.

The author is now with the Electricity Department in Wellington.

Foreword

OF ALL MAN'S WORKS the lighthouse is probably the most unambiguous, its purpose singular, its message simple: all is well, the way is clear.

Gaunt in its marine setting on island, cape or promontory the lighthouse is an outpost of civilisation, safeguarding and preserving man from his oldest adversary, and a thread in the fabric on which the whole of civilisation has been woven for centuries, that of trade between people and nations.

Yet oddly enough artists have not often found lighthouses worthy of paint and canvas, nor writers suitable items for pen and paper.

But considering lighthouses are in fact outposts, perhaps this is not surprising. They are not easy to reach. Their surroundings are often bleak, too-isolated capes and islands can be dangerous obstacles to ships and their crews, and lighthouses are warning signs to keep away the straying sailor or guide him safely past.

Because there are few accounts of lighthouses and those who tend them, whenever we mention we were lighthouse keepers we are asked a thousand questions.

Not only are there few accounts, there are also few lighthouse keepers. In New Zealand there are twenty-five lighthouses around the coast and forty-odd men and their families who look after them.

So it is even more inevitable we should be asked a thousand questions-in a population of three million how often could anyone meet a lighthouse keeper?

Although the questions vary between the intelligent and the extraordinary, they have a common basis: what did we do all day?

We had plenty to do all day and indeed it has probably been the busiest period of our lives so far, yet our questioners really have no idea of the truth of it even after the explanations. Charles Dickens, for instance, was far from the mark when he had Sam Weller saying, "Anything for a quiet life, as the man said when he took the situation at the lighthouse," and Albert Einstein's belief that a job at a lighthouse would be the ideal way to solve complicated problems was equally off-beam.

In some respects both Marita and I were already in tune with the lighthouse way of life before we started.

As a nurse, Marita had long learned to take things in her stride. Dealing with the sick, the dying and sometimes the dead, one must gain some cognizance of the ways of the world and the people in it. For that is what lighthouse life is-society in microcosm; put two or three couples and their families on an island together for a year at a time and you are bound to find the truth of it.

As a seaman, for me it was really only a matter of changing the way of my association with the sea. In the lighthouses I found much the same things that sent me to sea in the first place. The most I have required of life is that each day be different, a requirement well met at sea-too well met sometimes-I have spent the odd days in gaol for minor idiocies in various peculiar places and have been shot at in a South American revolution. But all in all life was satisfying.

Equally so in the lighthouse service.

There have been some who thought we had found a way of life that approached Paradise.

Certainly, Paradise, assuming it ever existed, is becoming harder to find in our self-created Utopia and sooner or later a man is driven to think he would like to live on an island and lie in the sun with the sea lapping at his feet.

We lived on islands and often lay with the sun overhead and the sea at our feet. But it wasn't Paradise. We still had our lives to live. And no man can live with himself, let alone others and still be in Paradise.

But for all that, we enjoyed the lighthouse life. Why else did we stay eight years? As a matter of fact, we left only because I was carried out on a stretcher.

And it all began with an Ancient Egyptian. ...

CHAPTER 5 -THE DISTRICT NURSE

Excerpt:

I appreciated the strength of women. There she was, heavily pregnant, clambering aboard a heaving ship with the spirit of the pioneers who once dashed about colonising everywhere in lace and frills. Only Marita was not in lace and frills, but in maternity slacks and a heavy oilskin which, had she missed her footing, would probably have drowned her.

I recall a similar episode at Cape Brett a couple of years later while we were on leave in Russell. One of the keeper's wives was returning to the lighthouse a week after the birth of her first child. I was aboard the Marine Department's launch Tainui for the trip out and to do a spot of fishing on the way home.

When we reached the lighthouse the sea was surging six feet up the rocks.

"Be a bit of a jump," the launchman said to Rae and her husband Frank who had come in to accompany her back from the hospital. They both nodded.

"We'll be all right," she said.

They climbed down into the lighthouse boat and their baby was handed to them in its carrier. When they reached the rocks Rae steadied herself and jumped as the boat surged up towards the rock ledge. She staggered a moment and then climbed quickly out of the water's reach. The boat dropped swiftly as the water retreated. As it surged back, the baby was thrown to the principal keeper's outstretched arms and handed to its mother who beat a quick retreat as the sea splashed up again.

"Need tough sheilas in the lighthouse business," the young launchman observed laconically, as Rae and her husband climbed with bent backs up the steep cliff track.

Some time later another Cape Brett mother had to have her child delivered by the lighthouse keepers themselves. The weather was too rough for the doctor and district nurse from Paihia to reach the station.

Instead, they had to be landed some miles down the coast and slog through thick bush and precipitous country. In the meantime the baby was born, fortunately without any complications. The department took a jaundiced view of the whole performance and was at some pains to express its disapproval that the event had not been conducted in a hospital in the proper manner.

Of course the baby had come several weeks earlier than expected-an event which happily, so far, anyway, is beyond the bureaucracy of government departments' control or influence. Lords they might be, but not yet gods.

But there was no doubt about it. Pregnant girls in oilskins climbing heaving ladders, newly-delivered mothers jumping onto wet rocks and climbing cliffs, or having babies while the doctor was lost in the bush-lighthouse sheilas needed to be tough all right!

The doctor examined Marita and asked why she had come in so early. There were still at least nine weeks to go. After her expostulation and then explanation, his sigh left no doubts as to what he meant but which, in the interests of professional ethics, he felt better left unsaid.

Two months later the time arrived for her to go to the hospital. She was on her own in an accommodation house in a wet Auckland winter. Her mother was in another country and I may as well have been in another world.

She timed her pains, picked up her bag, and walked to the hospital.

Alone.

The first I knew of anything was a short telegram from the matron that a son had been born that morning. I left the radio room and walked down the hill. Soon I would be able to eat something better than pressure-cooked Irish stew. God! did I hate Irish bloody stew! I wasn't much good at baking bread, either.

She and David came home three weeks later. Life resumed as orderly a course as was possible with a new baby in the house. Those who have experienced that condition will know what I mean.

Those who have not would never understand.

CHAPTER 8 - TINGLEY PETER

Excerpt:

The principal keeper that followed Dudley, Ray Johnson from Cape Brett, had a dog called Rowdy, an old fellow who one day showed signs of being substantially sick.

Since his mother bred dogs, Merv said he was the logical person to see that Rowdy was taken ashore to see a vet. Ray's wife was very fond of Rowdy-and Baby Lamb, and her geese Victoria, Albert, Miranda, Pegasus, and cats Tom and Jinkle-and she had definite misgivings about the proposition. But Merv's mother bred dogs, after all, and perhaps that was a more important consideration. The dog would surely be in sympathetic hands.

And so Rowdy and Merv sailed for Auckland with a five pound note to pay expenses.

Many weeks later a note conveyed the sad news that Rowdy had indeed been sick and it had been necessary to put him to sleep.

Included was a bill for seven pounds.

Ray's wife was highly suspicious but she paid up, although she never did work out, so far as we knew, how it cost twelve pounds to have a sick dog put to sleep.

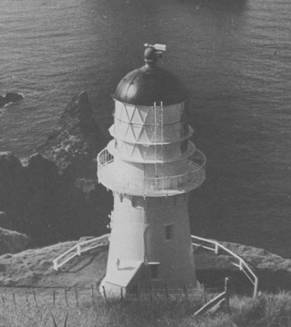

CAPE BRETT

The Cape Brett lighthouse stands nearly 500 feet above the sea on the cape named by Captain Cook in 1769 in honour of Rear-Admiral Sir Piercy Brett, a Lord of the Admiralty.

Today a 35-foot tower stands at this southern entrance to the Bay of Islands, which is one of New Zealand's world famous big-game fishing grounds. It flashes twice each 30 seconds with a visibility of 29 miles; along with Cape Reinga and Moko Hinau it guards the long stretch of coastline between the country's most northerly point and the approaches to Auckland, its busiest port.

The lighthouse, first mooted in 1906, began operation in 1910 and was unique in New Zealand in that its lens revolved in a mercury bath, which gave it smoother movement than the conventional bevelled rollers and ball bearings. The lighthouse was re-rigged in 1955 with a diesel-electric plant but was later connected to the national grid by a power line from the Maori settlement at Rawhiti, some miles to the west.

As well as a radio-telephone the station's two keepers and their families have a telephone land-link with Russell, from where they receive their mail and stores once a fortnight by launch.

Sometime in the next few years the station is to be converted to automatic operation and will then have no permanent staff. Its only visitors will be workmen and technicians on irregular maintenance and service visits.

Cape Brett was the scene of New Zealand's first outright shipwreck when the schooner Paramatta was blown ashore there in 1808 and her crew massacred by the Maoris.

The massacre was hardly to be wondered at-the crew had contracted with the Maoris to load various commodities aboard the ship. But the crew reneged on their part of the deal. To add to the indignity of it all, they threw the hapless Maoris overboard and fired at them, wounding three.

But on leaving the Bay of Islands on her way back to Sydney the ship was caught in heavy weather and driven on to the Cape. With a gale of wind and rightfully hostile Maoris, the crew stood no chance.

Photo supplied by Ministry of Transport